Take a look inside the boardrooms of corporate Canada and you’ll find that over the years, they’ve largely stayed (and looked) the same. While it has been proven again, and again, and again that a diverse executive suite directly contributes to the growth of a company’s bottom line and overall performance (and is just generally the right thing to do,) straight, white cisgender men have kept the c-suite looking pretty much the same for a long, long time. Wes Hall is working to change that.

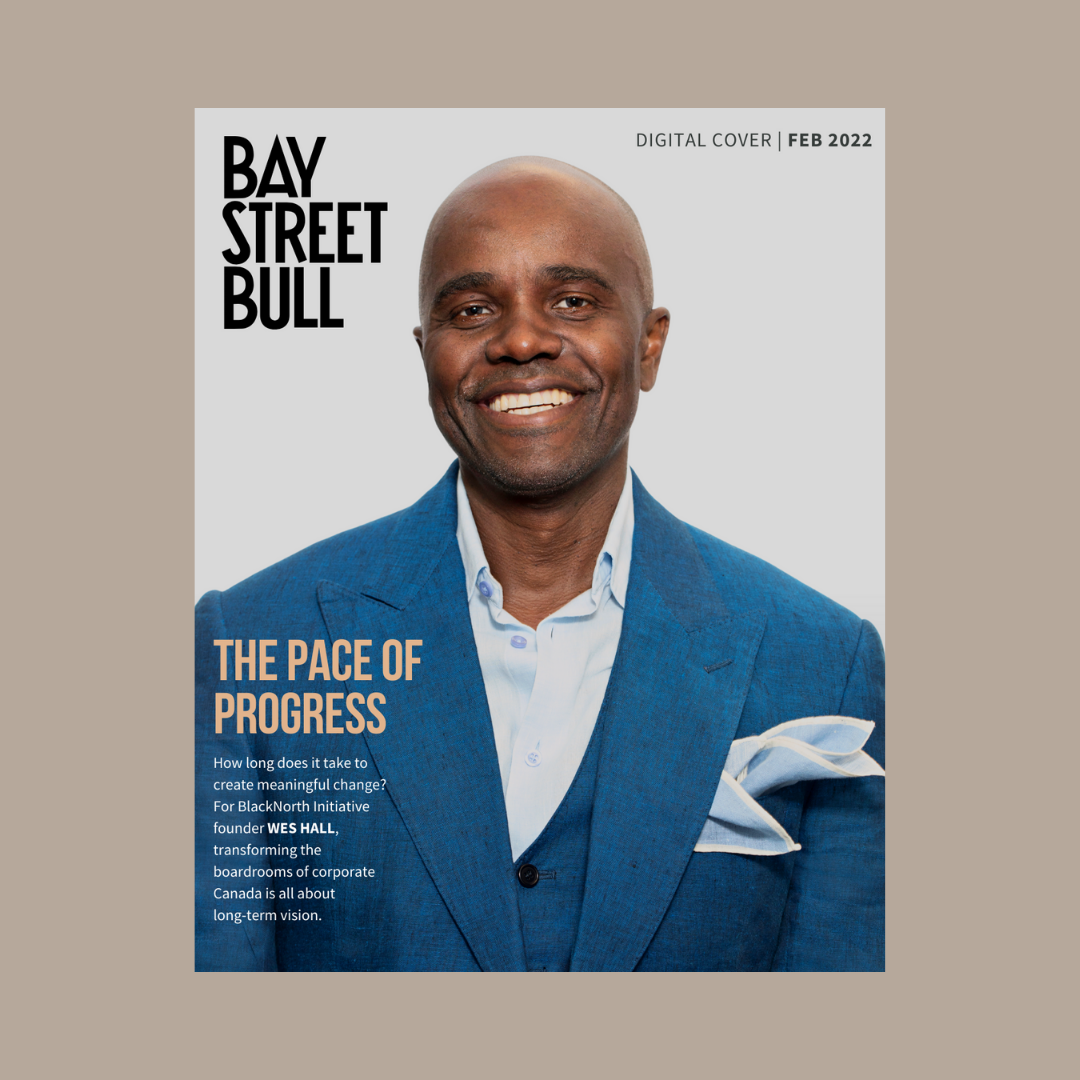

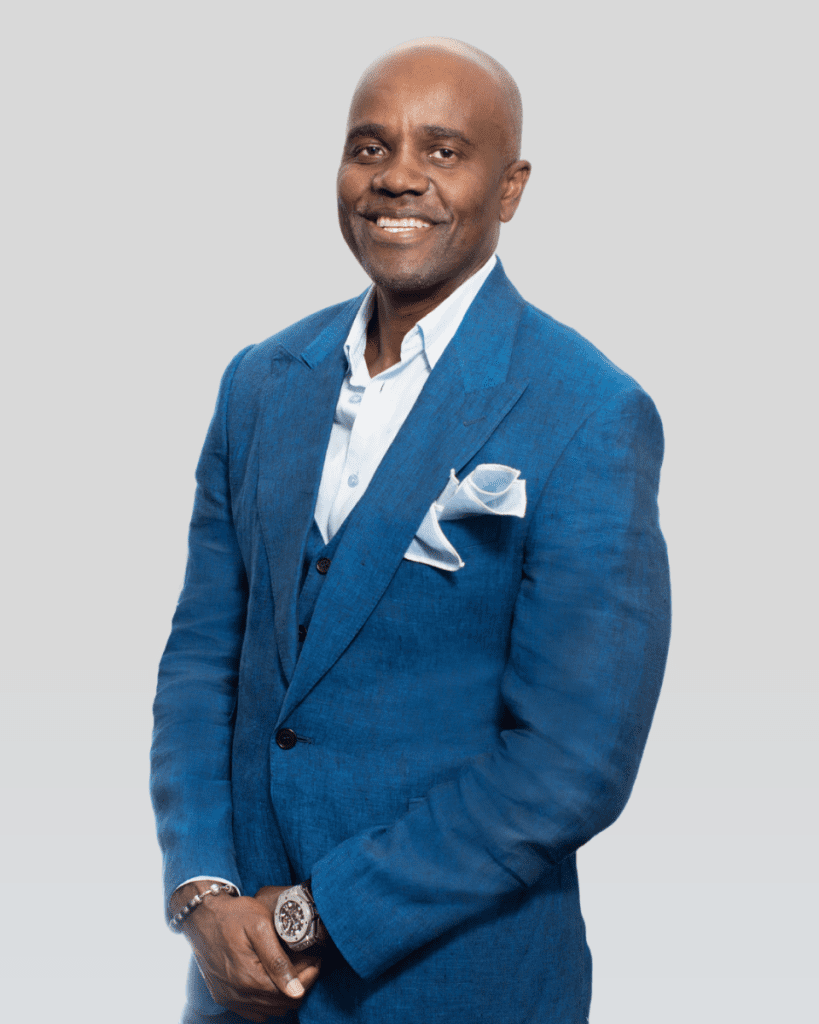

One of Canada’s most powerful figures on Bay Street, Hall is the executive chairman and founder behind Kingsdale Advisors, an investor on Dragons’ Den, and the founder of the BlackNorth Initiative—a non-profit whose mission is to end anti-Black systemic racism in the corporate world (and beyond).

In the wake of the George Floyd murder and Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, Hall was moved to take action by doing what he does best—by using business as a vessel for change. Specifically, by having the country’s top executives and companies commit to diversifying key decision-making positions.

Almost two years since he founded the non-profit, Hall covers Bay Street Bull‘s February 2022 digital cover to talk about BlackNorth, their new Racial Equity Playbook, and how long it takes to see progress.

(Prefer an audio format? Listen to this interview instead)

Bay Street Bull: What is the BlackNorth Initiative and why did you create it?

Wes Hall: Back in September 2018, I sent around a note over LinkedIn to a bunch of people, Black folks in particular, and said, “Hey, I want to form this group and use it to change the conversation with respect to how Black people are perceived in particular in the industry.” A number of people responded to it and we started talking about the fact that there’s a lack of representation on Bay Street. I called the group BlackNorth.

Then 2020 came. I watched the video of the George Floyd murder and immediately, I was struck by the inhumanity of it all. Here’s a man that was treated a certain way, and the only reason why he was treated like that was because of the colour of his skin. At the time, I was in my home office and I literally had a mirror in front of me. I looked in the mirror, and I saw George Floyd. I saw George Floyd because all I saw was a Black man reflected back at me, and I decided to write an op-ed for the Globe and Mail where I talked about my experience as a Black Canadian, and the various things that I go through just because I’m Black. I got calls from all these different business leaders saying, “I didn’t know that people like you experience these things in this country.”

It may seem naive when somebody responds that way, because those leaders would look around their boardrooms and see that there are no Black people. They would also look around their C-suites and realize that there are no Black people because 0.8 percent of the executive positions are Black—that’s a very, very small number.

RELATED: 5 Black Female Entrepreneurs Who Are Redefining Their Industries

So what does that mean? It means that if you’re really empathetic towards what I’m going through as a Black person, maybe you can be a part of the solution? And so I said, “Let’s form an organization and agree that we’re going to look at our own organizations as leaders at the top.” We’re going to look at the board first and see whether or not we have Black people occupying any of the board positions. If the answer is no, let’s agree that we’re going to mandate as CEOs that our business will do something about that. Because Black people represent three and a half percent of the population in Canada, we’re going to allocate three and a half percent of the board roles to Black folks. And while we’re doing that, we’re going to look at the C-suite and do the same thing. Then, we’re going to go right into the pipeline and look at the student population. We’re going to look at the sponsored dollars that we spend. Of every $100 spent on major charities in Canada, only seven cents are spent on Black-related charities. When we sponsor things and donate money towards causes, we’re going to make sure that Black Canadians are supported. Then we ask CEOs to sign a pledge. It’s not a company that’s signing, it’s the CEO saying, “As the leader of this organization, I am going to say that I’m committed to doing these things while I’m the leader of this organization.”

And that’s what we’ve done. We have close to 500 companies that have signed that pledge representing $1.3 trillion in value—and the numbers keep growing. Every day there are new companies that jump on board and say, “We want to do that.”

Bay Street Bull: During times of tension, we tend to see a lot of lip service in the business community. How can they be held accountable to implementing policy changes within their organizations so the DNA is fundamentally altered to foster sustainable change?

Wes Hall: You’re right; it’s the flavour of today, flavour of the month. We’ve seen this before with the civil rights movement in the ’60s, the ’70s, the ’90s with Rodney King. When Rodney King was beaten by LA police officers, there was this demonstration all over the world that had people saying, “We’re going to do something about it.” This time around, we need to do something different because that window seems to open every 30 years and we can’t wait around for it to open again. When you look at the BlackNorth board, for example, it’s made up of the most powerful and influential business leaders in this country. People who, when they say something, others listen. We know for a fact that a significant number of those companies have already started to do things and change. They’ve already started to put Black folks on their board. They’ve already started to put money in the Black community. They’ve started to loan money to Black entrepreneurs.

Bay Street Bull: How quickly can we expect progress, realistically? Change doesn’t happen overnight, so how can expectations be managed?

Wes Hall: These are big, massive companies and it’s almost like turning around a super tanker—it takes time [for change] to happen. Two years later, these companies that signed the pledge and the things that they’ve done for their size, it’s actually pretty impressive. Last year there were some articles written that said the movement isn’t fast enough, but we gave these companies a five-year commitment to make these changes. We certainly didn’t expect to see 30, 40, 50 percent of those changes within a year because these are massive organizations. They’re going to have to look for talent. They’re going to have to do all these different things to put systems in place to see the results of their hard work. I strongly believe that in the next year or two, you’re going to see monumental changes across the landscape for those companies who signed the pledge.

Bay Street Bull: How much of this is about the long-term vision?

Wes Hall: I’m part of the SickKids Foundation board, and our mandate is very simple: to make sure that we look after and provide quality healthcare for children. That’s it. This organization is built for that purpose but we don’t expect that they will just say, “Okay, we cured a bunch of kids. It’s been five years. It’s been 10 years. Let’s just disband this organization and move on. We’ve done our job.” Some of these things could take generations before we start to see results. It might miss our generation. We might never see it in our lifetime, but other generations will benefit from it. That’s the reason why you have to start at some point.

What we’re saying to folks is that we know this is a long-term vision. We set up an organization to cure anti-Black systemic racism. It’s not going to happen overnight because you’re changing attitudes. It’s going to take time; it could take generations before you change that. We’ve been dealing with systemic racism in particular for 400 years in North America. There’s a view that it’s going to be dealt with within five years or six years. No, it might not happen in my generation. If Dr. [Martin Luther] King [Jr.] was alive today, he would go, “Wow, I’m glad I started what I started in the ’60s because there has been movement as a result of what we started.” It’s the same thing with myself and others that are doing it today. In 30 years, we’re going to be looking back and be glad that we started what we did back in 2020 because we’re seeing the benefits now. It’s always incremental because we’re dealing with such large, ingrained issues that are very divisive in a lot of cases. To do that takes time to actually see the full fruits of the hard work that’s put into fixing something.

Bay Street Bull: BlackNorth recently worked with the Boston Consulting Group to create a Racial Equity Playbook. What are the key tenets of this playbook? Who is it helping? What kind of blueprint is it providing?

Wes Hall: That playbook cost $500,000 to put together and we are creating it for the benefit of those people who’ve actually signed a pledge. When companies say, “We would like our organization to be inclusive and diverse,” where do you start if you really don’t have an organization that’s inclusive and diverse today? What we’ve done with the playbook is give people a step-by-step approach to designing their racial equity strategy within their own organization.

Bay Street Bull: What is the difference between equity and equality?

Wes Hall: A lot of people don’t really know what those expressions really mean, and the differences between the two. Some may say that my organization is equal because we treat everybody the same way, but is it equitable? Does it take into account that we all started from different places? Do you treat me the same way as a guy who grew up in Rosedale, and I grew up in Malvern? If you do, you’re not being equitable. You’re being equal, but you’re not being equitable because you don’t take into account the fact that I came from a very tough neighbourhood, left my parent’s home when I was 18 years old, had to finish my education on my own, and work two, three, or four jobs to be able to do that. Whereas the kid from Rosedale just went to school, their parents paid for it, and they just have to focus on getting A’s. I did all those things, bucked all the trends, and got a B plus, but I didn’t get the job because I didn’t get an A. So, equity and equality should be viewed very differently in organizations. That’s what the Racial Equity Playbook does; it actually allows you to see the difference and to take into account people’s lived experiences, which is really key.

Bay Street Bull: We’re around the two-year mark since the start of BlackNorth. What have been some of the major milestones since the organization was founded?

Wes Hall: We’ve had 16 committees working very hard on different things. One of the things we’re really proud of is this homeownership bridge program. One of the biggest concerns that we’re hearing from people is there’s not enough affordable housing in Toronto. We know that a lot of wealth is created by owning your own home, but unfortunately, you can’t come up with a down payment. If you’re from an underprivileged neighbourhood, you don’t have the bank of mom and dad to rely on. We were able to work with municipalities, the governments, philanthropists, and builders to create a product that would get Black people—in particular, women because a lot of single mothers are Black women—in Canada access to buy and own a home without having to come up with a sizable down payment. We use this concept of sweat equity to come up with their down payment. What does that mean? We hear it often in business where you talk to a founder who is raising money and ask, “How much money do you have invested in your business?” To which they respond, “Sweat equity.” Well, sweat equity has value, and business people put a value on it. So why don’t we put the same value on sweat equity when it comes to homeownership?

For example, instead of single women coming up with $50,000 for a down payment, how about she donates her time in the community to help to improve the lives of others? That’s creating value to the community and value to her. That’s sweat equity. Now, once she owns her home, she’s now going to be able to leverage the equity built into that home to send her kids to university. And when those kids graduate with that university degree, they can come out of community housing and hopefully get that decent job whereby they can buy a home of their own. When you consider this mindset, it’s really about changing people’s thinking.

Wes Hall: The way that I look at it is that Black History Month should be 12 months of the year. Unfortunately, companies just go, “We’re going to recognize all these various groups once a year.” It should be something that’s in their consciousness all the time. I’m hoping that with Black History Month, it continues to highlight great work, not just the struggle. It is not only to highlight the struggles of what Black people went through in 400 years of slavery but it’s also to highlight the accomplishments of Black Canadians. Look at what they’ve done with one hand tied behind their back. Could you imagine if we remove that strain and let them compete equally and equitably? How much better would our society be? When we use the best of us to help solve problems, it solves a problem for everybody. And it’s not just Black Canadians; everybody’s going to benefit from the talent that we bring to the table when we’re inclusive.

Bay Street Bull: Where are we at today compared to two years ago, when you started BlackNorth?

Wes Hall: One of the things that I was so proud of was there was this Black man who owned a gym. He came to me and he said, “Wes, for the first time, I’m proud to be a Black man and a Black business owner.” For the first time. It’s the pride that this creates within people knowing that others are going to look at them differently, not with suspicion. That’s what makes us proud because we now know there is a way to [change] perceptions.

Bay Street Bull: You’re an investor on Dragons’ Den. What is the biggest observation you’ve made of the entrepreneurial community here in Canada and its potential? What advice do you often give to those who are pitching to you?

Wes Hall: Well, first of all, I practice what I preach. I became very, very successful by promoting, supporting, and investing in BIPOC entrepreneurs. Pretty much all my investments are behind BIPOC entrepreneurs and I’ve hit some massive home runs, I can’t even find the ball. That’s my secret sauce—I invest in people that others view as uninvestable. But I don’t want to be the only person to get all the success; I want others to get it too. I want others to experience how amazing these people are.

The beauty about discrimination is that you know when you’re being discriminated against. You walk in a room and you know that you are not [welcome] there, or you’ve got to figure out a way to get these people to like you because the only reason they don’t is because of the way you look. Being on Dragons’ Den means I get to open the doors for a lot of people who look like me and show them that this is possible. So, when BIPOC entrepreneurs go in front of me, it’s a no-brainer. If I have a track record of doing very well investing in BIPOC entrepreneurs, why wouldn’t I look at them favourably when they come to me on the show? If they come and present well, their numbers are backed up, and they answer the questions appropriately, they will always get my investment. Always.

Bay Street Bull: What’s the bigger picture for you?

Wes Hall: You know, before when I was younger, I would say, “I want to make enough money to buy a car and a house, get married, and have a few kids.” That’s the goal that I kept. I have a house and I have a few cars. That’s the material aspect but I didn’t have the humanity aspect and now I’m able to build that. It turns out that that part is the most important part for me today—how can I change people’s lives for the better, today? How can I make sure that when I pass, I leave this world a better place? And that people go, “This person did certain things that advanced others.”

One of my good friends once said, “Wes, when you come from poverty, you become a first responder. And your role is to go back into poverty, and pull as many people out as you possibly can.” Once we achieve a certain level of worldly success, what do we do with that? If we do nothing, then that’s not success in my book.